Norwegian Kelp

The good, the bad and the ugly

Still we find pristine blue forests; tangle kelp forests with diver. ©Aleksander Nordahl

6 January 2025

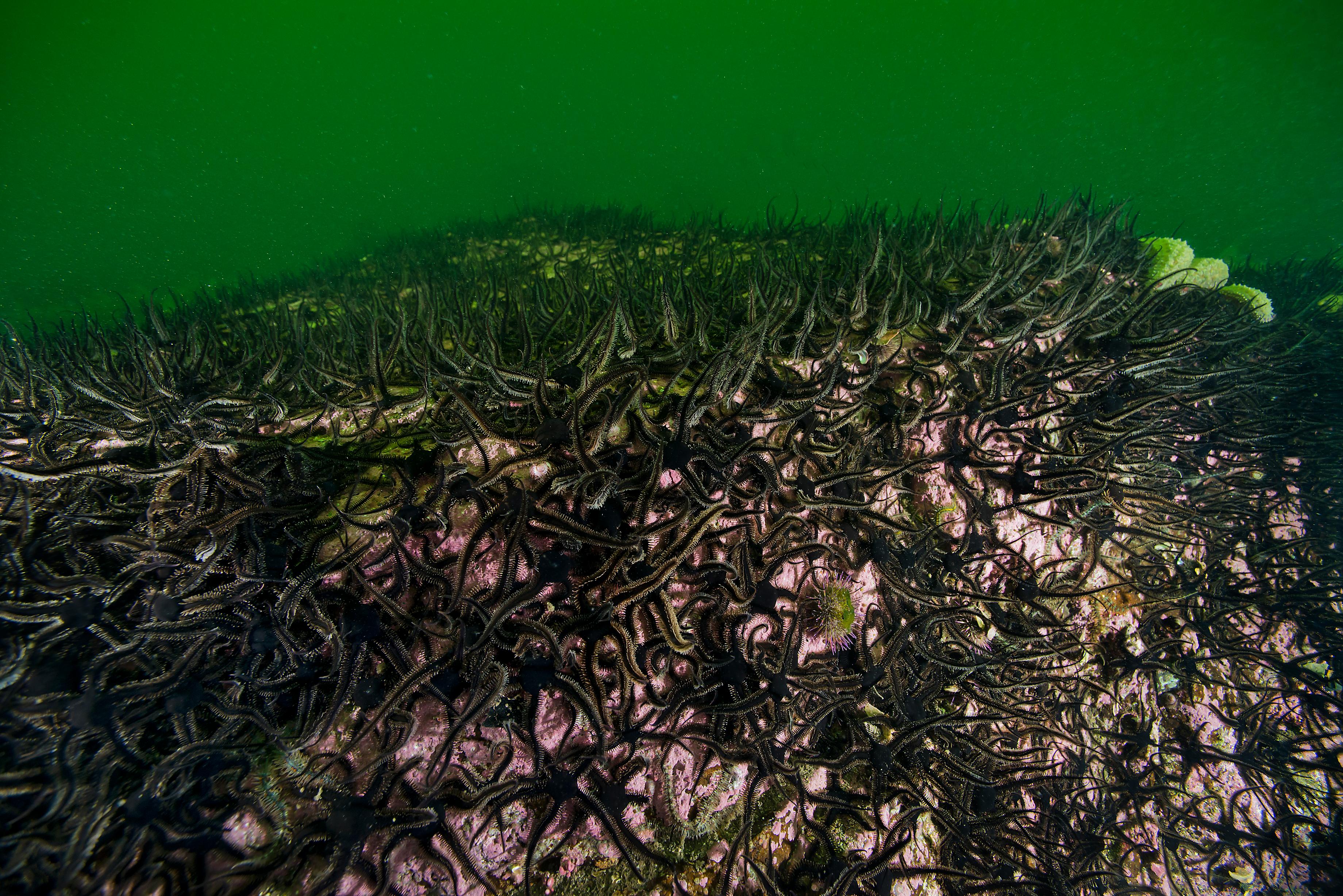

Exploring the pristine waters of western Norway, you may, in many places, be disappointed. Go for a swim and you may become entangled in the Chorda filum seaweed lines, which may also foul your boat propellers. Any form of recreation, as well as marine biodiversity, will also be disturbed by the ugly filamentous algae. More recently, the appearance of long-spined, white sea urchins has created problems for bottom-dwelling life, not to mention barefoot wading. If you enjoy rich and diverse marine life, you may be disappointed by dense accumulations of black brittle stars that create a patchy covering in coastal habitats (“back in black”). Perhaps you are longing for the good old days and wonder where these bad guys have come from. Observations suggest discharges of nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic waste (faeces) from fish farms have caused these proliferations.

Good, bad, ugly: Who's who

During recreation at the coast, people fancy the pristine kelp forests with all its colours, fish and diverse marine life. These forests maintain during all seasons year after year, they are the good.

In many places along the coast, the kelps and other bottom living organisms have been turned into sea urchin barren grounds. Sea urchins graze everything, can persist for decades, and leave no other visible life on these bottom deserts. The sea urchins are really the bad.

During the last decades our blue forests have been overgrown and subsequently replaced by different species of opportunistic, often slimy, filamentous algae (known as turf, or "lurv", in Norway). They are also primary producers, and can create habitats for a few animals. But flourishing in summer, then rotting in winter, they are really the ugly for both marine life and recreation.

Shifting between the bad and the ugly

Recently, white sea urchins were observed all the way up to the surface, populating rocky shores where sugar kelp should be expected. In the past few years, these urchins have been observed in high densities from five metres below the surface, but they have never been as abundant all the way up to the surface as, for example, in Tomrefjord. In the summer they migrate to deeper waters, being replaced by dense beds of filamentous algae. The following winter season they move back, and begin grazing towards shallower waters.

Is this unique to Tomrefjord? No! We now see the same trend in several fjords on the Norwegian west coast.

From desert to forest in one year?

When sea urchins explode in density (as they have done in many countries) they can change rich underwater forests to desert-like bottoms that can persist for years. Sufficient removal of urchins, either by human actions (restoration) or by predators (crabs, fish, otters) make hard bottom surfaces available for seaweed recolonisation. In Norway, kelp forests have recovered quickly and formed dense beds of different kelp species within only one year after sea urchin removal.

These underwater forests are highly productive, but to achieve the status of a rich underwater “rainforest”, both diversity and organism density must recover. It seems that many of the fauna components take longer time to establish, probably due to differences in colonisation rates, a recovery time that can be even longer if their predator species come first.

So, tend and maintain your restored kelp beds to let all species have time to settle and grow.

Share this story

- Ecosystems and habitats

- Threats

- Ocean of hope