Lines in the soil

Farmers fight to reclaim a freshwater future in coastal Bangladesh

The village of Shinghortoli is deeply divided along this line, between paddy and shrimp farms. ©GM Mamun

15 July 2025

There is tension in this village by the river; along a stark, straight line. One moment, dark grey aquaculture ponds, glistening in the sunshine, stretch to the horizon. Then, you cross the line, and the landscape comes alive with lush green paddy pocked with bright yellow sunflower plantations in the distance.

We’re in Shinghortoli, a village of five hundred families in the southern coastal subdistrict of Shyamnagar in Bangladesh. An embankment keeps the river out of the habitation during high tide, and doubles as a dirt road—the village’s main artery. Usually a bumpy two- or three-wheeler ride, a good rain makes it impossible to traverse except by foot.

An embankment keeps the Chunkuri River out of the village during high tide. ©GM Mamun

Since the 1980s, the salinity of the ocean has been creeping deeper inland. Dams and bridges weakened the river’s downflow, and the ocean’s tides pushed brackish water further and further upriver. Ever intensifying cyclones battered and breached the embankments. Saline water intruded, ruining freshwater crops.

Finding agriculture increasingly difficult, farmers began letting the salty river water into their fields, converting them into aquaculture ponds to grow bagda, or black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) for the export market. Once saline water gets in, it spreads to surrounding paddy fields, rendering them barren. So, like dominoes, paddy fields across the coastal belt of Bangladesh flipped over to aquaculture.

The ecological disaster was an economic miracle.

- Naushad Ali Husein

The salt gradually transformed the environment. Freshwater ponds and aquifers became salinised (Akter, 2023). Livestock declined. Trees died (Ray et al., 2021). But the ecological disaster was an economic miracle.

Aided by trade liberalisation policies and structural adjustment programmes, shrimp exports ballooned (UNEP, 1999). At its peak the shrimp industry provided 1.2 million livelihoods, accounted for more than 4% of the national GDP, and brought in an annual export income of over US$500 million—becoming the country’s second-largest exporter after garments (EJF, 2014).

But now, bagda is on the decline. The coastal belt is seeing a wave of locally organised movements to convert aquaculture ponds (ghers) back to agricultural land. Singhortoli is in the midst of such a transformation—and therein lies the conflict.

Turning tide

Choto Babu’s gher is dry to its cracked, lifeless bed. It’s time to fill the pond and set out fry (juvenile shrimps, in their post-larval stage). But the paddy farmers aren’t letting the shrimp farmers draw water from the Chunkuri River.

Ever since Al Amin Hossain can remember, his own family—and all of Shinghortoli—had been drawing water from the Chunkuri to cultivate shrimp. In the beginning, the profits were glorious. But over time, extreme weather, oversalinisation, drought, and disease began taking their toll.

The biggest culprit has been the white spot syndrome virus, which spreads quickly, and kills the shrimp before they reach adulthood. Shrimps are sensitive to heat, and as temperatures have crept up in the coastal belt (Jahan et al., 2024), so has the prevalence of this virus, which regularly costs many farmers their entire season’s investment.

Al Amin was also frustrated by a pest—a small snail with a hard shell that settles on the farm bed. “They’re almost impossible to get rid of. We emptied the whole pond, and removed every last one by hand. But as soon as we started a new crop they would take over again.”

Another problem is the quality of the fry. In the early days of shrimp farming in Bangladesh, the supply came from the neighbouring mangrove forest, the Sundarbans. At the time, this was encouraged by the government and international development community. “There are apparently vast areas in the mangrove forests, supposedly rich in seed supply, that are still lying completely unexploited,” says a 1986 government report supported by the Food and Agriculture Organization and UNDP. The report estimates up to 3 billion juvenile black tiger shrimp had been taken from the forest in 1985.

After years of overexploitation, they are not as abundant. Catching shrimp fry in the wild is now outlawed, even though it continues openly. It is easier and cheaper to get them from hatcheries. But farmers complain that fry from hatcheries are not nearly as resilient, and susceptible to disease.

Aquaculture ponds for shrimp farming have taken over the coastal landscape in Bangladesh since the 1980s. ©GM Mamun

Then there were natural disasters. To make it easier to draw water from the river, many shrimp farmers bored holes in the embankments, and put in sluice gates. This weakened the embankments and left communities vulnerable to saline water intrusion during cyclones and tidal surges.

Hundreds of kilometres of embankments crumbled during the Cyclones Sidr (2007) and Aila (2009). The tides swept through villages, killing people, contaminating freshwater ponds, destroying homes and crops—including 38,885 hectares of shrimp farms—and fuelling anger against the shrimp farmers in their communities (Tajrin and Hossain, 2017, Subhani and Ahmad, 2019). Subsequent storms have had equally catastrophic results. After Cyclone Amphan (2020), some villages remained exposed to tidal flooding for nine months.

Many of these communities were already angry because of bullying tactics employed by influential shrimp industrialists in the past. Ever since its early days, the industry was characterised by intimidation, vandalism, harassment, misappropriation of land (including reserve mangrove forests)—and even murder (EJF, 2014, Paprocky and Cons, 2014, Mahtab, 2020).

Al Amin Hossain's debut sunflower plantation was a picture of promise.

Green wave

Al Amin displays no resentment, though, when he tells us his story. His ready smile and shy, youthful manner make it difficult to picture him taking such a hard stance against the shrimp farmers.

About four years ago, faced with persistent losses, he and his neighbours decided that they would no longer cultivate shrimp. But switching back to paddy was complicated. It would not work without unanimity. If anyone in the neighbourhood continued pumping river water into their farm, all the surrounding farms would be affected by the salinity, and their crop might fail.

“If you want to see the sunrise, you can’t see it at night; if you want shrimp, you can’t get rice,” says Abdullah Al Rifat, Shyamnagar subdistrict’s assistant commissioner for land. He says he has had a number of cases where some farmers want to switch, while others don’t.

“According to the SA&T Act, the owner of a piece of land has the right to decide what it will be used for,” says Al Rifat. “So long as the activity is legal.” But if each person does as they wish, then the paddy farmers can’t grow anything—and that leads to unrest.

If you want to see the sunrise, you can’t see it at night; if you want shrimp, you can’t get rice.

- Abdullah Al Rifat, AC (Land), Shyamnagar

So, the administration consults the stakeholders and elders in the community, and eventually sides with the majority. Usually, it’s majority by ownership. Meaning, if only 30% of farmers cultivate shrimp, but own 70% of the land, the administration sides with them. Generally, shrimp farmers own more land, so this arrangement favours aquaculture.

Al Amin and his allies mobilised, lobbied the administration, and took out demonstrations. Like a wave, the fields began flipping to green.

Agriculture being more labour intensive, Al Amin had to downsize his operation. He previously leased 25 bighas (a bigha is about a third of an acre) for aquaculture, with a group of partners. “When we went back to paddy, we left that lease and now we’re all farming on our own land only.”

On four bighas, he needs 24 units of labour through the tilling, planting, transplanting, and harvesting stages of a crop. “So that benefits 24 people. But as a shrimp farmer, I benefited alone.”

It usually takes a few monsoons for salinated land to become suitable for agriculture. The initial crops can be poor. But Al Amin saw success right away. Shinghortoli is blessed with an abundant freshwater aquifer, and Al Amin says he turned a profit from his very first crop after switching. With help from various NGOs, he planted mustard and other crops. His debut sunflower crop is a picture of promise, with large, beaming faces buzzing with bees. Officials from BRAC have put up a sign on his plot boasting the success of their seeds.

The green wave stopped at Nasrul Hassan’s plot. The shrimp farmers beyond this point have refused to switch. Nasrul has dug a freshwater canal several feet wide as a buffer between his paddy field and the gher beside it. “They were supposed to stop using saline water,” he says. “After suffering losses for two years, I dug this to protect myself.”

Nasrul Hassan has dug a canal along the edge of his plot to act as a freshwater buffer between the shrimp ponds and his farm.

Al Amin is determined to prevent salt water from entering the land by any means—even though his own land is several plots away from the dividing line. “Perhaps today I will not face losses. But somebody else will, and they will be forced to switch [to shrimp]; and then the next one... eventually it will get to me. But today if I support the movement, it will grow.”

Lines in the soil

When we return a month later, Choto Babu has somehow succeeded in drawing river water into his gher. Paddy and shrimp farming continue side-by-side, but there are problems on either side.

The oppressive March heat, before the arrival of the rains, is a trying time for shrimp. Monohar Mondol’s shrimps are dying. “I’m struggling to keep enough water in the gher,” he says. Choto Babu’s pond, adjacent to his, which has been bone dry for months, has been soaking up his water. “The paddy farmers even object to drawing water from the shallow well.”

The next morning, we find Monohar stooped—over a paddy field, instead of his gher. He has leased half a bigha to plant paddy over on the green side of the line. But he now doubts if the effort was worthwhile.

“Since I planted, I haven’t been able to rest. All my time has been spent tending the paddy field. I haven’t had enough time for the shrimp.” The crop on the field next to Monohar’s has entirely failed because of salinity intrusion from the adjacent canal during a particularly high tide. Even Al Amin’s poster child of a sunflower plantation has not been spared.

Monohar points out that this land has been growing freshwater crops for three years, and yet, it isn’t free of the threat of salinity intrusion, and neither does it have guarantees of a good crop.

Successful shrimp farmers dread going back to agriculture, which is a life of backbreaking work and incessant worry. Monohar explains one person can single-handedly operate 10 bighas of ghers. So, shrimp farmers spend almost nothing on labour. This significantly reduces their investment. Meanwhile, a paddy harvest seldom brings in more than BDT 20,000 (EUR 145) in revenue per bigha—which barely covers expenses; where a shrimp farm can easily bring in as much as BDT 70,000 (EUR 500).

Mohohar admits that shrimp output is a matter of luck. But he and his neighbours have overcome the odds, and continued making profits, unlike Al Amin and his friends. They have no reason to switch to paddy. In fact, switching would bring about a significant decline in their living standards.

“Ours is an open economy, and people will do what is profitable,” says Al Rifat.

Shrimps are sensitive to temperature, and the March sun and dryness are taking their toll.

No way back

Unlike Shinghortoli, many villages have permanently lost their freshwater ponds and aquifers to salinisation. They have no prospects of switching back.

Abdus Sabur Gazi’s village, Aatir Upor, is about 5km from Shinghortoli. It has no freshwater ponds or aquifers to support freshwater agriculture. But he longs for the days before aquaculture.

“Before there were ghers, each house had two to five cows, lots of ducks and chickens,” he says “There were freshwater fish in the ponds. Now you don’t find these.”

Before the advent of shrimp farming, locals would produce vegetables, pulses, oil, and freshwater fish, alongside rice, says Dr. Fazle Rabbi Sadeque Ahmed, a climate change expert and deputy managing director at PKSF, a government institution for the alleviation of poverty through employment generation. “With this entire ecosystem, even a small sharecropper could get by. Because of the saline water, [...] we have become solely dependent on shrimp and crabs.”

If a freshwater farmer’s crop fails, they will still be able to salvage some of their investment from the hay and from other crops. “But if a shrimp farmer’s crop fails, the entire investment is lost,” says Abdus Sabur. “They’ll have to take a loan to pay back the hatchery.”

The risk of successive crop failures can only be borne by those who have sufficient capital. Because if farmers can’t repay their loans, they’re forced to sell their land.

“It is the people who have large amounts of land and capital that are growing and benefiting [from shrimp],” says Dr. Ahmed. “Now small farmers and marginalised people have no source of income. They are migrating. It is creating conflict in the society.”

“When people are leaving the shrimp industry, it’s not just because of environmental awareness,” Al Rifat. “It’s 10% awareness and 90% economic gain. It’s become that you either make a lot of money or if you’re hit by the virus, you lose everything.”

But financial problems are often caused by ecological realities.

The decline of the black tiger shrimp

Industry researchers say Bangladesh’s shrimp exporters have failed to leverage the full potential of black tiger shrimp as a premium product in the global market. They have cited low technical performance, and lack of certification or bio-security standards. Certification and standards are difficult to ensure due to fragmentation and lack of traceability in the supply chain.

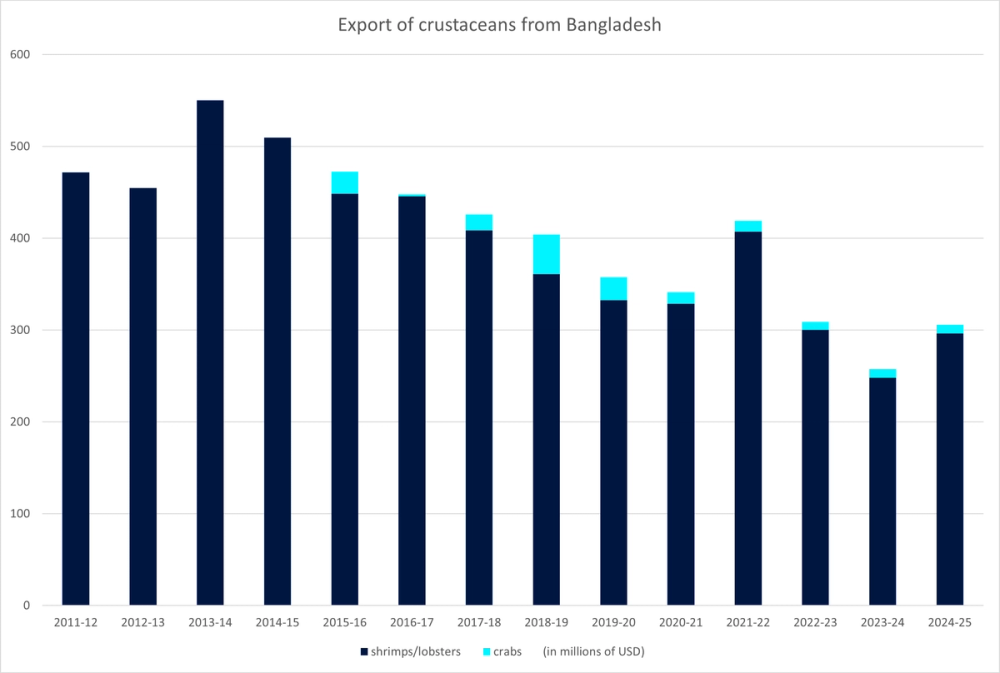

Shrimp exports halved from 2014 to 2024. Production has declined by almost 30%, and Bangladesh’s global market share has dropped from 4% to 2%. Shrimp processing plants have been shutting down or sitting idle. Like Singhortoli, many villages have seen movements to shut down aquaculture. But for farmers, the transition back to freshwater agriculture hasn’t always been easy or peaceful.

Trend of export income from shrimps and other crustaceans from Bangladesh. Source: Export Promotion Bureau

“Salinity is an asset,” says Tushar Majumdar, senior fisheries officer of Shyamnagar subdistrict. Paddy can grow anywhere in the country, he says. But marine aquaculture is a specialised possibility in the coastal districts, because of their salinity.

He points out that shrimp farming has brought wealth to the region, including to farmers. Speaking with local farmers, it is difficult to deny that many farmers have improved their lot by farming shrimp—despite reports by international organisations like Environmental Justice Foundation showing that fry collectors and farmers, who occupy the bottom rung of the supply chain, benefit relatively little from the enormous export revenues (2014).

“People are moving away from shrimp, but not necessarily from aquaculture. Other salt water products, including soft- and hard-shell crabs, are on the rise,” insists Tushar. “The Department of Fisheries is working to improve hatcheries.”

Industry researchers say that there is still potential for Bangladesh’s shrimp business to recover and excel. In 2021, the Department of Fishers applied for the Geographical Indicator (GI) certification to recognise it as an exclusive national treasure of Bangladesh. There are also ongoing efforts to produce the non-native king prawn (a.k.a. Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei), which has a higher productivity and resilience to disease than black tiger shrimp.

But these measures don’t address the underlying problems impacting farmers and their communities.

Our natural resources are soil, water and air. If we spoil these, we kill the goose that lays the golden eggs.

- Dr. Fazle Rabbi Sadeque Ahmed

The true cost

“Per unit area, the income from ghers is much greater than that from paddy,” says Dr. Ahmed. “But if you think of it holistically, [...] our natural resources are soil, water and air. If we spoil these, we kill the goose that lays the golden eggs.”

The profits from shrimp don’t take into account the accompanying ecological and social impacts—an enduring water crisis, unemployment, food insecurity, biodiversity loss, and social unrest. If they did, would the industry still be as profitable as it is?

“We’re reaping immediate benefits, but we’re destroying the water, the soil, the food chain,” says Dr. Ahmed. “Today there’s one virus, tomorrow there will be another. Day by day, things will get worse

“For each fry that is collected, ten other creatures are thrown out as bycatch. We don’t recognise the importance of these species, but in the ecosystem, they have a role. And we are destroying them.” These losses are often not recoverable, he says.

Some farmers have shifted to crab farming, which is now bringing profits. But this, too, has ecological impacts and associated risks which must be studied. “We are exploiting natural crab stocks without regard for their ecosystem,” he warns. “The average crab mass of wild stocks in the forest has declined from 200gm to 35gm.”

With the rise of crab culture, the average size of wild crabs has drastically declined, according to climate expert Dr. Fazle Rabbi Sadeque Ahmed.

So, what’s the solution?

“At this moment, because it is earning foreign currency, the government can implement a zoning system. Areas where intrusion has happened can be dedicated to shrimp and crab farming. [...] And it should be done following an environmental impact assessment.”

But for now, communities must work out their own paths towards figuring out what they want to produce. Assistant commissioner Al Rifat explains that the local government cannot implement a policy without instruction from the national level. “The subdistrict administration implements policies passed by the central government. We do not have any direction on this issue to-date.”

For his part, Monohar Mondol admits that paddy farms might flourish where he is presently farming shrimp. If they decide to, a switch is viable. In fact, he says the shrimp farmers have been deliberating doing just this. “Following this monsoon, we will plant paddy.”

Nasrul Hassan is unconvinced. “They say that every year. Let’s see what happens.”

Share this story

- People and the sea

- Ocean of hope