One artist's hope for the ocean

The art of seaweed

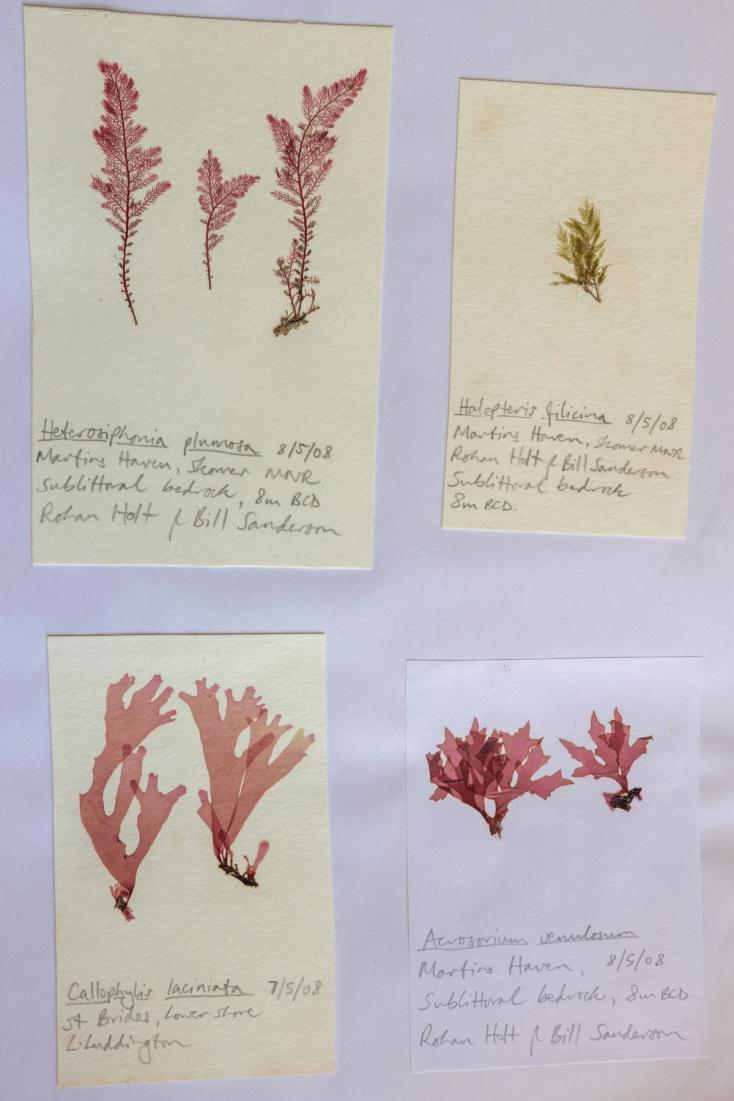

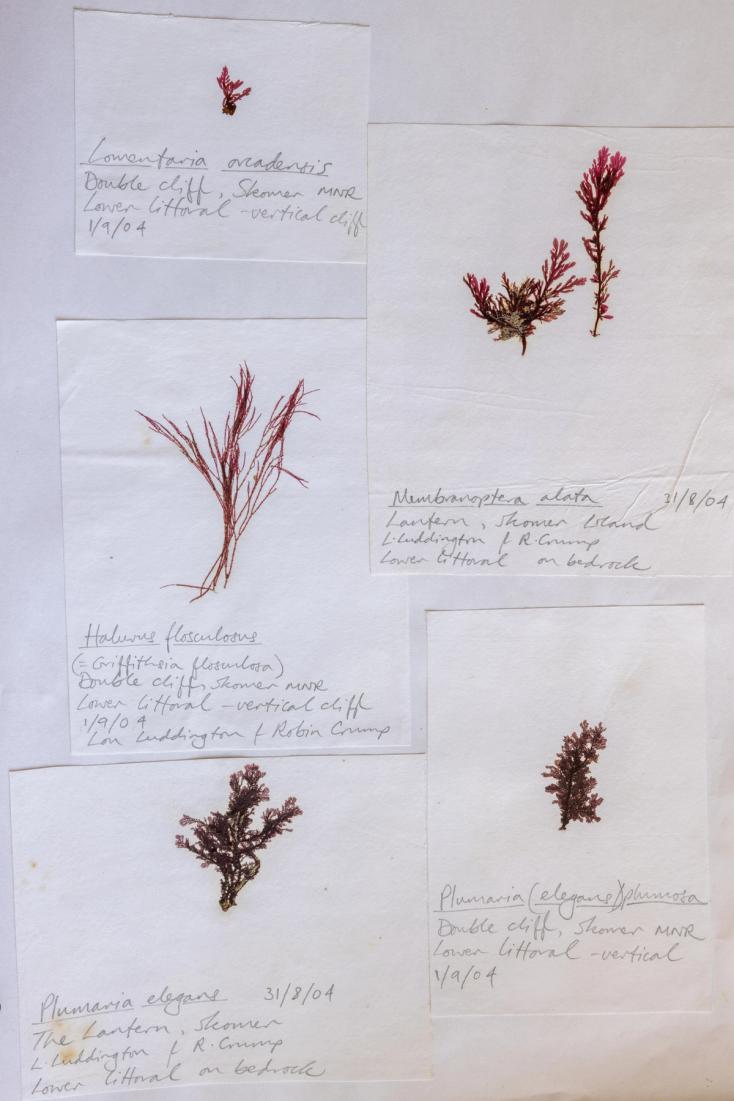

A collection of Molly's seaweed art laid out in her kitchen studio

27 June 2025

Buoyant with sparkling eyes and a rippling mane of hair that glows the colour of kelp, I meet local artist Molly Macleod at her stall at the Wales Festival of Seaweed in Pembrokeshire. I’m captivated by her bright collection of seaweed artworks. Pressed seaweed framed into exquisite wall hangings, photographic prints of seaweeds developed with seaweed extracts and cyanotype prints of ghostly white seaweeds in a sea of Prussian blue.

Warm and enthusiastic when talking about her work and particularly seaweeds, she finishes her sentences with a giggle. “As well as making my seaweed pressings I work with scientists, mostly ecologists and biologists on collaborative multisensory projects. Oh, and I run seaweed pressing workshops, hee hee hee! ”

Molly is an environmental artist who reveals hidden worlds through creative scientific exploration. She creates art from seaweeds collected along the Pembrokeshire coast.

I’m familiar with the practice of creating herbarium collections of pressed seaweeds from my early days as a marine biologist. But this was for identification purposes rather than art. So when I hear Molly is running a seaweed pressing workshop later in the week, I’m drawn to attend by a wave of nostalgic curiosity. I’m intrigued to know how she approaches it and whether the process is any different.

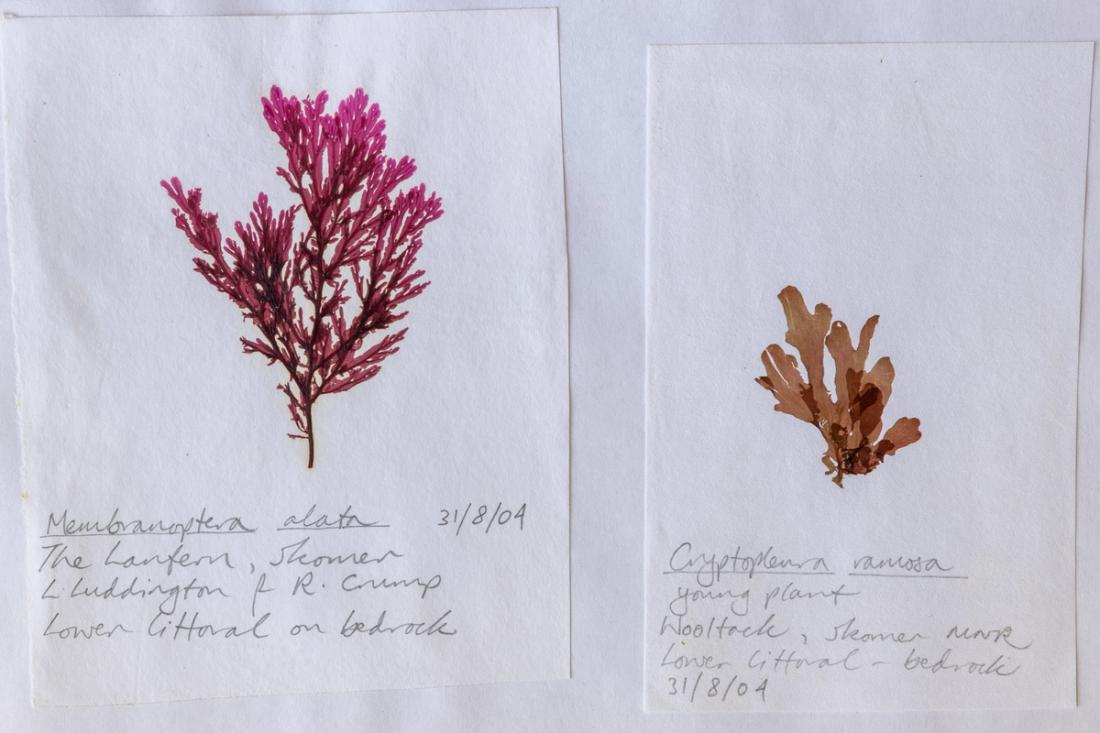

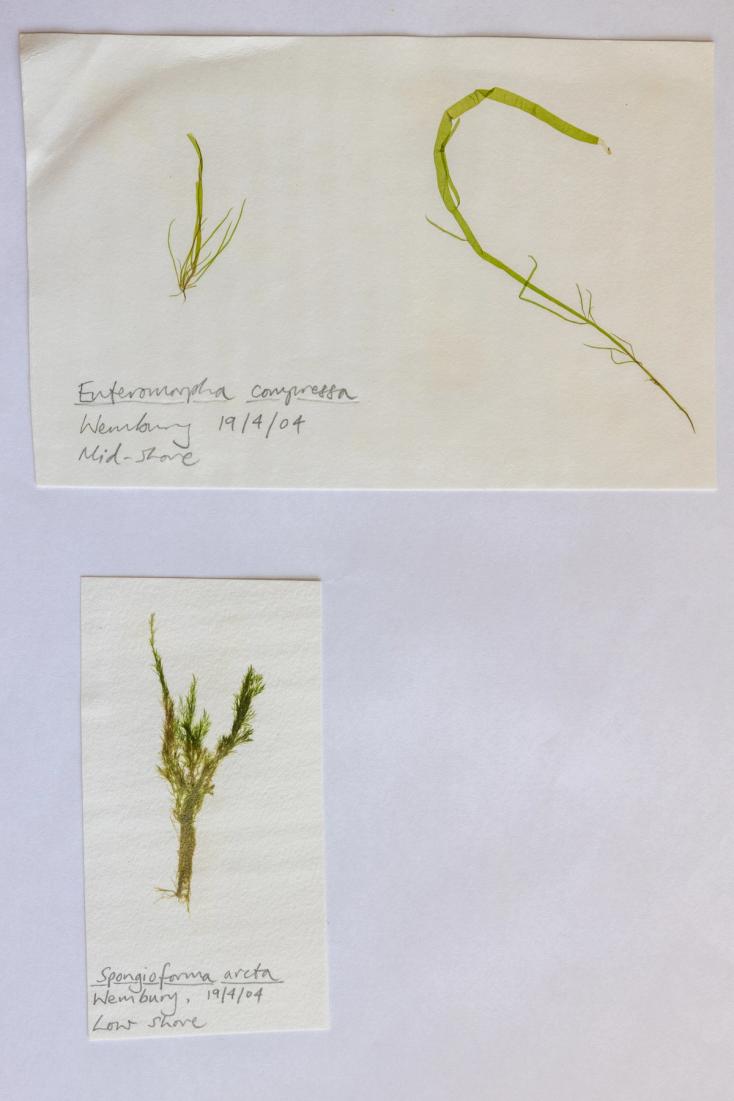

Part of the author's British seaweed herbarium, dating back to 2004.

We meet at the beach at low tide, a gathering of 13 ladies plus one gentleman, the partner of one of the attendees. I notice this gender skew when Molly tells us how pressing was popular in 19th century Victorian Britain. Considered an activity that was unlikely to rouse the spirits, it was a socially acceptable pastime for women. As a result, many natural history museums contain vast collections of meticulously catalogued pressed seaweeds that date back hundreds of years. Not only do these provide historical records of species diversity and distribution, but through modern methods of chemical analysis they allow scientists to show how the ocean is changing (Miller et al., 2020).

Meanwhile we titter at names like cockscomb, erect clublet and Cutler’s many cleft weed, and reflect on how seaweeds do indeed have a secretly scintillating life cycle of eggs and sperm and sexual reproduction. Molly is free with her knowledge of how, when, where and which seaweeds are best for collecting and pressing, “The plan is to scan the beach as the tide drops and wade in the shallows for detached weeds. I would recommend collecting the fine red ones, thick specimens don’t tend to press so well.’’

Following Molly’s lead, we peel off socks, stuff them in our shoes and leave them high above the tide line. Strolling towards the water's edge, delighting at the soft sand squeezing between my toes, I realise this is about so much more than pressing seaweeds. The act of mindful searching and collecting is soothing in a way only nature can provide. The gentleness of the day begins to seep into those around me too and I can feel their shared peace in these low tide surroundings.

Handily stashed in the pocket for impromptu seaweed collecting, dog poo bags are the perfect size for carrying wet seaweeds. Molly passes them around, one each for our hand picked treasures. Once filled with a hoard of fresh seaweed they have the same weight and feel as a scooped poop but with the appealing tang of the sea, and the promise of something much prettier.

Back in the classroom, Molly provides each person with a flat tray filled with freshwater for floating and admiring their collections. Using a fine watercolour paint brush she demonstrates the art of manoeuvering the fronds and branches of each weed into natural shapes. Once satisfied with the arrangement, a piece of thick watercolour paper is gently pushed into the tray and angled beneath the seaweed, and carefully lifted so the water can drain.

The paper is then laid to rest on layers of absorbent newspaper and cardboard. The final stage is to press the seaweeds flat beneath a stack of books. Left untouched for a few days the result is a fusion of seaweed and paper that can be framed as ocean art, a still-life made of light and pigments and sea minerals.

Curious to see more of Molly’s work I arranged to meet her a few weeks later at her home studio. Breezing through the open door on a warm summer’s day I enter a naturalist's emporium. Her kitchen is alive with artwork in all stages of progression and experimentation. Seaweeds hang from the ceiling in desiccating ribbons, some twisted into braids made supple with the application of glycerine. Others are pressed flat and framed to decorate the walls like sea flowers, intricately branched and coloured bright crimson and pink. Wooden printer trays and glass cabinets brim with treasures—shells, bones, exoskeletons, driftwood, dried flower stems and seed heads, and curious radial impressions on paper. “These are mushroom spore prints,” Molly reveals.

She tells me about her latest work entitled Evolve that imagines the moment before ecosystem collapse, a haunting collection grown from sprouted grass seeds in the shape of human faces. Molly describes it as “a vision of our speculative ecological future, where rising CO2 levels have pushed root structures into excessive growth, and plants have evolved to mirror human anatomy in a final cry for our empathy.” Its rendition is powerful, wispy roots meshed together into a series of masks. Lined up on her kitchen counter, these were the ones that didn’t make the final cut for the exhibition organised by The Climate Emergency Network and University Of The Arts London at the Lethaby Gallery in London.

Molly in her studio kitchen, a naturalist's emporium of work in progress.

I’m most drawn to what she’s laid out next to them though. Bright skeletal sculptures familiar in form if not colour. I recognise the gnarled branches of kelp holdfasts, “I’ve been casting the holdfasts of different types of kelps using plaster of Paris. I like to show the beauty of forgotten or unseen things,” Molly tells me. In living kelp the holdfast anchors the stipe and fronds to the seabed with its many branched haptera. These root-like structures grow into tiny crevices in the rock and are glued fast by sticky sugars, creating a powerful, multi-faceted bond. Many are wrenched from the rocks by heavy storms and swell and end up stranded on the shore.

“When I find the holdfasts washed up on the beach, they look alien but at the same time familiar. I see the patterns in their structures as a reflection of patterns in the human body, ” Molly explains.

The intricacies of a kelp holdfast cast in plaster of Paris.

Exploring her studio provides an intriguing insight into how her observations in nature have inspired experimentation and a deeply thoughtful creativity. As I browse, she asks if I’d like to hear some sound recordings she made from plunging a hydrophone into a rockpool. “It has to be a calm day otherwise the background noise from waves and wind overpowers any other sounds. This was from a calm day.” As she hits play a thundering, rhythmic scraping fills the room. My mind puzzles over what could make such a sound, then it hits me. “Limpets! That’s the sound of limpets licking rock, isn’t it?” I exclaim. I’ve heard it before, whilst crouching on the shore at low tide, but not amplified to fill a room. These conical marine snails feed by drawing their rough tongue called a radula over the rock. The radula has many tiny teeth, much like a wood file, that scrape off a layer of algal growth and seaweed sporelings creating an audible rasping.

There were other sounds too, whirring, buzzing, clicking—a cacophony of creatures at large in their tide pool. Some of these sounds would be used for communication, others simply the creak and groan of daily activities. This recording became part of an interactive sound installation called Silent Seas created for the Ocean Lab aquarium, in Goodwick. Silent Seas invited the audience to drop a pebble into an amplified artificial rockpool whilst listening to Molly’s sound recording from the living pool. The act of each viewer adding their own visual and sonic disturbance to the installation, encouraged them to consider their impact on wider coastal habitats. Thoughtful homage to the hidden creatures of Pembrokeshire’s tidal pools.

Research shows that beholding art, art experiences and enriched environments can trigger positive chemical reactions in the body. In their book Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us Magsamen and Ross (2023) illuminate the power of the arts and aesthetic experiences. They report that engaging in an art project, no matter your skill level, for as little as 45 minutes reduces the stress hormone cortisol, and that just one art experience per month can extend your life by ten years. The human brain is hard wired to take joy from the arts. We are physiologically moved by beauty.

Although the hard facts of statistics and science may prove that the ocean needs our help, the emotive, aesthetic power of art has the ability to stir us profoundly and launch us into action. In this case, the allure of seaweeds as art and ocean ambassadors. Molly aims to deepen our understanding and connection with nature through her work. “By showing the hidden beauty in nature, I hope to inspire wonder so that people will care more and feel compelled to look after the natural world.”