Near collapse to resurgence

Return of the Salmon: Hada River’s success story

The salmon are back. Wild salmon in the Hada River following the removal of open net salmon farms.

18 June 2025

In the winding bends of the remote Hada River, pink salmon flash beneath the surface like sparks of flint. As recently as 2020, fewer than a hundred returned. In 2022 and 2024—these salmon return to their birth river on a two-year cycle—they numbered in the tens of thousands. No hatcheries intervened. No riverbanks or spawning grounds were rebuilt. The fish farms that had been laid across their migratory path for decades were simply removed and the salmon found their way home.

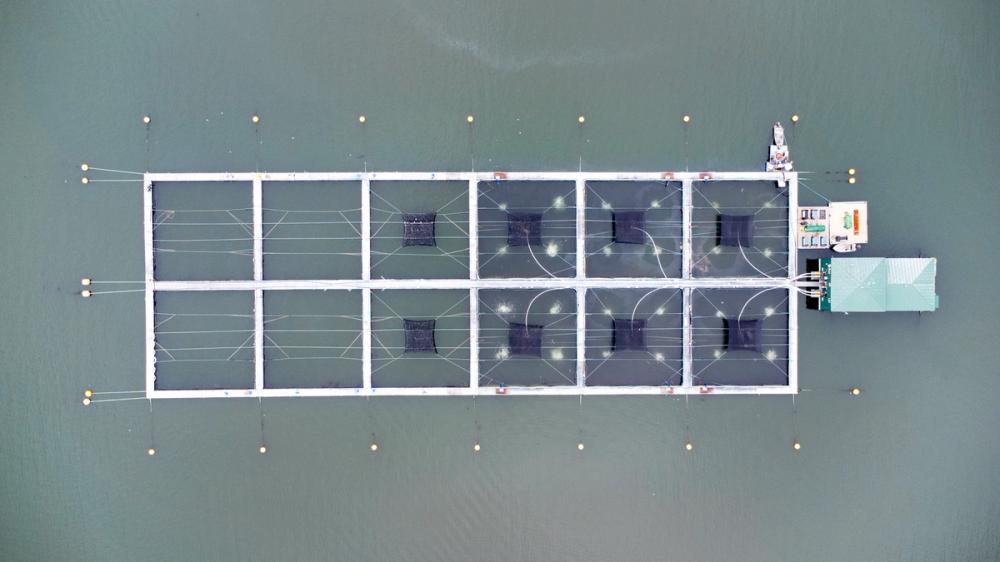

To date, fifteen open net salmon farms have been removed from the Hada River watershed region.

Open-net pen salmon farms—massive cages containing hundreds of thousands of Atlantic salmon—have dotted the coast of the western Canadian province of British Columbia (BC) since the late 1970s. These farms allow waste, parasites, and disease to flow freely into surrounding waters and the migratory paths of wild salmon. While they’ve been defended by industry as sustainable aquaculture, they’ve sparked decades of controversy and protest. In 2017, a wave of indigenous-led resistance, including the occupation of farms in the Broughton Archipelago, prompted government action and ultimately led to the removal of 15 farms from the waters of the Kwakwaka'wakw people.

A wave of indigenous-led resistance in 2017, led to the removal of 15 farms from the waters of the Kwakwaka'wakw people.

I first visited the area in 2017 during those occupations. I was there with my camera, drawn by the courage and resolve of the indigenous matriarchs and land protectors who stood their ground. I’ve been coming back ever since. For the last three years, I’ve lived on my sailboat Estera, based out of Alert Bay, documenting life above and below the surface as a freediver, photographer, and filmmaker. I’ve spent countless hours underwater watching salmon swim through kelp forests and seals dart through eelgrass. I’ve listened to elders around campfires and shared meals with families who’ve lived on these waters for thousands of years. My work, my heart, my very existence—they’ve all been shaped by this coast.

Sailing boat Estera provided a perfect platform for documenting the story unfolding in the waters of the Kwakwaka'wakw people.

This article is an act of service. For the public, yes, but also for myself. Like many, I’m trying to make sense of conflicting facts, government spin, and passionate voices on both sides. I’m trying to learn. I’m trying to listen.

"I thought we were going to lose them," says 72-year-old Brian Wadhams of the Kwakwaka'wakw nation. "And yet, here they are. We did nothing to bring them back. You give them half a chance, they rebuild. That’s what they do."

This resurgence in northern Vancouver Island is a rare good news story for BC's wild salmon—creatures whose significance goes far beyond their scales. They feed forests and bears. They are an integral and irreplaceable part of indigenous culture, ceremony, and trade. They symbolise resilience in the face of collapse. And now, they’ve become the centrepiece of a growing debate: do open-net pen salmon farms belong on this coast?

Hada River tributaries wind their way from open fjords through the forest, carrying the wild salmon to their breeding grounds.

Two scientists. Two views. One species.

Dr. Gary Marty, a senior fish pathologist working with the BC Salmon Farmers Association, maintains that the dangers of salmon farming are often overstated. "The potential for transfer of disease to wild fish exists, but it’s not the whole story," he told me. "Wild salmon are used to these diseases. The impact is exaggerated."

It’s a view shared by much of the aquaculture industry, which often positions salmon farming as a sustainable solution to growing seafood demand.

But Dr. Gideon Mordecai, a marine disease ecologist at UBC, challenges that narrative. "Yes, salmon have lived with pathogens for millennia—but not under farm conditions. Density changes the whole game. There are peer-reviewed papers showing this. The farms are amplifiers." (Krkosek et al., 2024)

Mordecai points out a structural issue, not just a biological one: "The burden of proof in Canadian fishery science often falls on those questioning industry, not those benefiting from it. That’s not neutrality. That’s a system built to maintain the status quo."

In a world of conflicting expert opinions and well-funded public relations campaigns, how is the public supposed to know who to trust?

Salmon as sovereignty

For many indigenous communities, the conversation is not just scientific or environmental. It’s existential. It’s about autonomy.

Isaiah Robinson, deputy chief councillor of the Kitasoo Xai’xais nation, leads one of the few indigenous-owned aquaculture operations in BC. Based in the remote coastal village of Klemtu, a full day's ferry ride to the closest city and one of the more remote communities in Canada, his community operates several fish farms that provide local jobs and revenue.

"Over half of our economy is based on aquaculture," Robinson says. "Without this, we crumble. Without aquaculture, we lose everything."

He doesn’t dismiss environmental concerns. But he insists that a blanket condemnation of salmon farming often ignores the specific context of communities like his.

"There are other opportunities, always," he adds, "but it has to be something real. You can’t just say ‘go find another job’ to a community like ours and walk away."

And he’s right. Even if wild salmon returns continue to rebound as they have in the Hada River there’s no guarantee that will translate into immediate, comparable jobs for remote communities. While a restored salmon economy offers hope for cultural and ecological wealth, it may not easily or quickly replace the stable, year-round income that aquaculture jobs have provided.

Without aquaculture, we lose everything.

The federal government’s transition plan gestures toward support for affected communities, but concrete details and funding commitments remain thin. For places like Klemtu, the fear isn’t just losing aquaculture, it’s being left behind entirely.

He also points to an often-overlooked mental health success story:

"We have almost complete employment in our village," Robinson says. "And we haven't had a suicide in many, many years. That’s something I’m proud of."

His pride is grounded in broader patterns. According to community reports, Klemtu’s indigenous-owned economic initiatives have led to some of the highest employment rates among remote coastal First Nations in BC, with estimates often cited above 90 percent. While direct mental health statistics for Klemtu are limited, research consistently shows that indigenous communities with greater control over their economy and governance experience markedly lower rates of suicide compared to those without such opportunities. (Chandler & Lalonde, 2018)

From collapse to rebirth

Wadhams remembers when the farms first arrived in his territory over three decades ago.

"They said it would be good for us. But we saw our beaches change. The water changed. The clams changed. And the salmon disappeared."

He’s spent the last few decades documenting those changes, fighting to have the farms removed, and working alongside scientists like Alexandra Morton to restore balance to the coast. The rebound of the Hada River salmon is, for him, a vindication.

"You come here four years ago, you wouldn’t see a single fish. Now, you’ve got thousands. That’s not a theory. That’s reality."

Wadhams sees salmon not just as food or biology, but as kin. "They feed the trees. The bears. The medicines. Us. You lose them, you lose it all."

The government’s transition plan: A double-edged sword

In June 2024, the federal government pledged to phase out open-net pen farms in BC waters by 2029. For environmental groups, this was a long-fought victory. But the reaction on the coast has been mixed.

"Five years to transition to land-based or closed-containment in my territory is the same as shutting our operations down," said Robinson. "We’re still not clear what the government means by ‘responsible transition’. It’s felt one-sided."

From my conversations it’s clear that while the plan is ambitious, it lacks the financial commitment and community consultation necessary to make it truly equitable. It risks repeating the very harm it aims to address.

Protesting open net pen salmon farming in the Broughton Archipelago.

Wadhams sees it differently. "We’re chasing the dollar all the time. But that dollar isn’t going to bring back the salmon. What brings them back is getting out of their way and letting them return."

The plan may be in place today—but in a volatile political landscape, nothing is guaranteed. As recent history has shown, even widely-supported policies can be walked back or watered down depending on who’s in office.

For communities—both human and ecological—who depend on salmon, the uncertainty isn’t abstract. It’s the nature of their very existence.

At the end of the day

The Hada River doesn’t know about politics. It doesn’t care about permits or press releases. But it responds to pressure. Remove the farms, and the salmon return. Give them space, and they come home.

"We don’t need to save the salmon," Wadhams says. "We just need to stop killing them. They’ll do the rest."

And in that simple truth lies a path forward—for the fish, and maybe, for us too.

Remove the farms, and the salmon return. Give them space, and they come home.

As I reflect on the stories I’ve heard and the waters I’ve swum through, I still have many questions. Some facts remain muddy, and not every voice agrees. But underwater, watching a salmon swim past my lens, the difficulty of understanding these complex issues fade and empathy takes over. Even with so many forces shaping their fate, resilience remains the salmon’s gift to the world. What responsibility do we have in return?